By Eloisa Rodrigues, June 2021

Why do museums collect art? How do they decide what to acquire? Can collecting practices be reimagined to challenge the knowledge museums produce? Can acquisitions serve as tools for decolonial work? These are some of the key questions that guided the roundtable discussion “Let’s Talk: Art Museums and Contemporary Collecting Practices”, held on May 20, 2021. The event was hosted by the Centre for Researching the Institutions of Art (CrIA) at the School of Museum Studies, University of Leicester. It was organised by me, Eloisa Rodrigues, in collaboration with Stacey Kennedy and Federica Mirra, and funded by the M4C DTP.

The recording of the event can be accessed here.

The aim was to create an informal and open space for museum professionals, curators, PhD students, and academic researchers to explore new ways of thinking about how public art museums collect objects. The discussion was grounded in presentations by three guest speakers: Eleni Ganiti, curator at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens (EMST) and PhD researcher at the University of Leicester’s School of Museum Studies; Dr. Lucy Bayley, postdoctoral researcher at Tate on the project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum; and Nikita Gill, curatorial trainee at the Institute of International Visual Arts (INIVA) and Manchester Art Gallery, working on the Future Collect project. Contributing further to the discussion were Uthra Rajgopal, independent curator and South Asian textiles specialist, and Yang Chen, PhD candidate researching museums without collections in Japan. Dr. Isobel Whitelegg, Director of Postgraduate Research at the School of Museum Studies, moderated the event.

This article summarises the key points raised by the guest speakers.

Please note:

Unless stated otherwise, quotation marks refer to the speakers’ presentations.

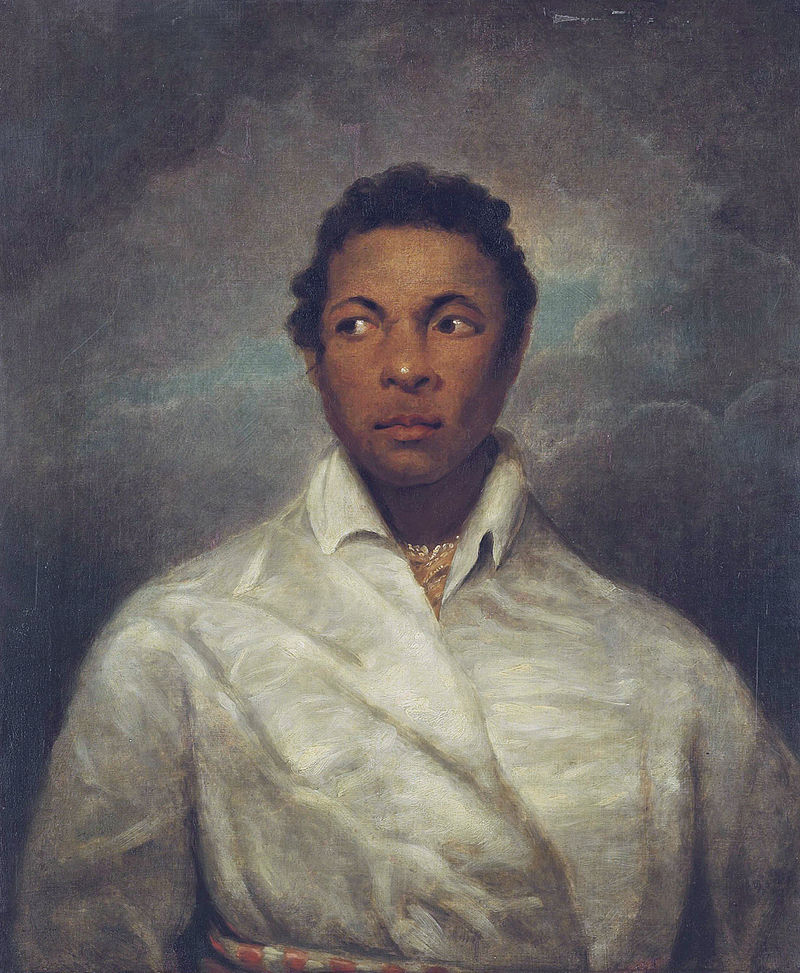

Cover image: Painting of Ira Aldridge by James Northcote, Manchester Art Gallery.

Collection Policies

Eleni Ganiti’s presentation examined the context in which the collection policy of the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens (EMST) was developed, where she works as a curator. Her talk began with reflections on the challenges of collecting contemporary art. On the one hand, collecting the contemporary challenges the conventional notion that museums are institutions for preserving the past. On the other, it questions the temporal assumption that value must be proven over time before an object is deemed collectable. Contemporary art museums, therefore, preserve the present—not a “time-tested masterpiece that has survived” a historical or cultural epoch.

Eleni argued that establishing a contemporary art museum allows us to reflect on multiple temporalities and contributes to mapping and understanding our current moment—not only as individuals but in relation to the past and future. This process adds a layer of critical thinking, as museums play a significant role in writing the history of art. The art they collect is what becomes available for preservation, appreciation, and research. Quoting Margaret Tali (2018), Eleni noted, “Through musealisation, art becomes heritage.”

In answering the question “How do public museums collect contemporary art?”, Eleni focused on two main aspects: first, the constant revision of theoretical approaches in response to shifting perceptions of contemporary art; and second, practical considerations such as available budget and space. These factors, she emphasised, vary by institution. Understanding the context in which an institution’s acquisition policy was developed—placing it within a specific time and space—helps reveal its priorities and aims.

EMST, established in 1997 and opened in 2000, has a collection policy built around two temporal axes: one defining contemporary art as beginning in the 1990s, and another including historical works dating to the latter half of the 20th century. The museum’s mission is:

“…to preserve and promote artworks by Greek and international artists that belong to the history of contemporary art, as well as works representing various contemporary trends—Greek or international—with an innovative and experimental character.”

“The museum’s objectives are fulfilled through the creation of collections in painting, sculpture, installation and multimedia art, drawing, engraving, photography, video, audiovisual works, other technological media, industrial design, and related fields.”

A key feature of these objectives is the intention to position modern and contemporary Greek art within a global context. Eleni noted the effort to remove Greek art from perceived isolation by reframing it through international perspectives. However, she also pointed to an internal contradiction: referring to artists from “metropolitan centres and peripheries alike” may imply that Greece’s national art scene sees itself as peripheral—an issue that deserves deeper reflection, particularly in a country whose ancient past dominates its historical narrative, often overshadowing its contemporary cultural production.

EMST’s contemporary art collection was built from scratch, which allowed the institution to shape its own identity. However, contemporary art has not traditionally been a priority in Greek cultural policy, resulting in a limited acquisition budget. The museum initially relied heavily on donations from artists and private collectors. Still, donations were accepted only if they aligned with the museum’s objectives and enriched its collection. Eleni noted the ethical dilemma in accepting donations from artists the museum should ideally be supporting. Acquisitions also take place through purchases, bequests, permanent loans, and commissions. Permanent loans are sometimes used to fill gaps in the collection.

Eleni concluded that revisiting the history and goals of a museum provides a valuable opportunity to reassess collecting and acquisition policies. Museums of contemporary art face unique challenges in constantly responding to the ever-changing present. In such a fast-paced world, the act of slowing down—explored in the next section—may offer an alternative approach.

Practising Slowness

Lucy Bayley’s presentation focused on “slowness” as a practice, informed by her work on Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum, particularly with four artworks by Ima-Abasi Okon acquired by Tate. She asked: “What happens when you slow down? What do you gain sight of?”—a question inspired by learning from artists, artworks, and their ecologies.

The Reshaping the Collectible project aims to contribute to theory and practice in collection care, curation, and museum management. Over the past three years, it has examined six case studies, including works by Tony Conrad, Ima-Abasi Okon, Richard Bell, and others, as well as thematic case studies on archives, documentation, and reproducibility.

Lucy summarised the research questions guiding these case studies. Selection is made by an implementation group (composed of collection care managers) and approved by an advisory group. The questions reflect the idea that understanding the past is crucial for shaping the future—suggesting that history is not linear.

Some of the key questions included:

- How does an artwork unfold over time?

Artworks often evolve in form once in a collection. If they change, which variation should be exhibited? - What are the boundaries between an artwork, a record, and an archive?

Performance-based works, such as Tania Bruguera’s Tatlin’s Whisper #5, require documentation each time they’re enacted. Is this documentation part of the artwork? Is it created by the artist or the institution? How should it be preserved? - Why do some artworks behave in “unruly” ways, and how can museums respond?

This concept, from sociologist Fernando Domínguez Rubio, contrasts the relative “docility” of paintings with the unruliness of installations or web-based art, which may require input from programmers or engineers to display. - How do we care for and sustain the network around an artwork?

This involves recognising collaborators who contribute to the making of a work but are often invisible in institutional narratives. - How do we make the invisible visible?

This involves questioning the hierarchy within museums, where curators dominate knowledge production, often sidelining conservators, registrars, audience services, and others. - Are we collecting histories or practices?

Lucy cited the example of Gustav Metzger’s Auto-Destructive Art, which challenges notions of preservation. Is recreating a destructive artwork a contradiction?

One of Lucy’s central takeaways was the need to democratise curatorial power and open acquisition practices to broader participation and transparency. This involves acknowledging the often-invisible labour that sustains museums and engaging those who are historically excluded from decision-making.

To do this, the project team has drawn on Domínguez Rubio’s Still Life: Ecologies of the Modern Imagination at the Art Museum, which explores how museums function through often-invisible labour. As a result, the team began conducting interviews with artists and collaborators and involving interpretation teams in acquisition discussions.

Practising slowness, Lucy argued, offers a way to reflect on the labour, structures, and values that shape museum practice. It also invites pauses in a fast-paced system—especially crucial during the pandemic, when institutions like Tate experienced redundancies and disruption. Slowing down allows institutions to learn, re-evaluate processes, and improve documentation for future generations.

As Lucy concluded:

“Slowness is a refusal to fall into the way things are. We could mobilise slowness as a chance to question and reshape—not just what is collectible—but museum practices and how they affect those involved. It’s not about fixing, but letting things breathe.”

Overcoming Obstacles of Representation

Nikita Gill’s presentation focused on her work as a Curatorial Trainee at INIVA and Manchester Art Gallery through the Future Collect project. Future Collect seeks to create a new, inclusive model for collecting and commissioning art in Britain—one that addresses systemic barriers to representation and avoids tokenism.

Tokenism, Nikita noted, often manifests when institutions address racism by merely acquiring or displaying artworks featuring Black subjects, without systemic change. Future Collect emerged in response to the Black Artists and Modernism (BAM) project, which audited artworks by Black and Asian artists in UK public collections. One of BAM’s outputs was the exhibition Speech Acts: Reflection-Imagination-Repetition, co-curated by artist Sonia Boyce. This exhibition questioned what museums collect and why.

Boyce’s collaborative work Six Acts, part of that exhibition, included a performance by artist Lasana Shabazz as Ira Aldridge, whose portrait by James Northcote (1827) was the first painting in Manchester Art Gallery’s collection. While the painting’s artistic merit was the reason for its acquisition, Aldridge’s biography—his migration from New York to England and career as a celebrated actor—was historically neglected. Nikita emphasised that we must move beyond surface-level inclusion and honour the fullness of such figures’ lives.

In 2018, INIVA hosted a study day on collections and acquisitions, which led to the development of Future Collect. As Nikita explained:

“The project was designed to create new models that support the transformation of collecting in British institutions—working with regional museums to commission artists of African or Asian descent, born or based in the UK.”

Over the past year, Nikita collaborated with artist Jade Montserrat and Manchester Art Gallery on the upcoming exhibition Constellations: Care and Resistance. Montserrat’s work, which blends activism and art across media, will be shown alongside collection works to generate new connections and narratives. The title Constellations reflects the idea of curiosity: discovering new stories and perspectives in the vastness of art history.

Due to internet issues, Nikita’s presentation was briefly interrupted, but upon resuming, she shared key questions:

- Who decides what is displayed—and who is forgotten?

- How can decision-making processes be unlocked and rethought?

- How can institutions move beyond performative gestures toward real transformation?

Nikita concluded with a powerful reflection on transparency across all aspects of museum work—from acquisitions to interpretation. Much work remains. But she left us with crucial questions:

“How can artists, integral to developing collections, be given space to engage with institutional and systemic racism? How can audiences feel empowered—not just represented on a wall, but as active participants in shaping institutional missions, values, and policies?”

References

Tali, Margaret (2018), Absence and Difficult Knowledge in Contemporary Art Museums. New York/London: Routledge.